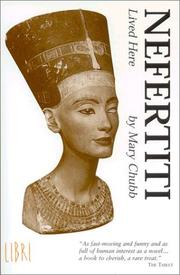

I've just finished reading Mary Chubb's (1903-2003) "Nefertiti Lived Here", and I feel compelled to write about her story. Chubb worked as an under secretary for the Egypt Exploration Society in the 1920's, and in 1930 she joined the Tell el-Amarna expedition, directed by John Devitt Stringfellow Pendlebury (1904-41). Pendlebury, though relatively young (aged 25) at the time, was also the director of the excavations at Knossos.

|

| John Pendlebury |

During the Second World War, Pendlebury was sent to Crete with the status of Vice-Consul, but in reality he was to organize the Greek resistance to the impending Nazi invasion which happened in 1941. Pendlebury was well trusted all over Greece, and possessed knowledge of the varying Greek dialects of the villages scattered all over the island. He organized many efficient and successful guerrilla groups, but Chubb describes that he was unable to achieve his full potential due to a lack of resources.

What happened next is harrowing. Chubb writes:

"On 21st May, 1941, the skyborne invasion of Crete, launched from the south of Greece, began. John left his office in Heraklion and, with one of his agents, set out to reach the guerrilla meeting point to the West of the town. They were cut off and surrounded by landing parachutists and John was badly wounded [by a shot from a Stuka]. He was carried to a roadside cottage, the home of another agent, whose wife and sister did what they could for him. German soldiers searched the cottage and took away his identity disc. From this the German officers knew very well who he was, and the next morning the soldiers came back with their orders. One witness told later of John's execution outside the cottage and of his proud bearing at this last scene" (P180).

Pendlebury was propped up against a wall, and shot by German soldiers in the head and chest. He was buried nearby, but was later reburied 1km outside the western gate of Heraklion in the cemetery at Souda Bay (Grave reference 10.E.13). So not only was Pendlebury one of the foremost archaeologists of his time, indeed the "first hero of modern archaeology", he died heroically trying to prevent his beloved Greece from German invasion. This is a little known story, and though it is a very sad and tragic one I would like to help make it as widely known as possible.

Rosalin Janssen(Birkbeck)has,i think,debunked the myth of Pendlebury being executed by the Germans after finding original correspondnace from his wife on the subject. He was wounded fighting the Germans but died of brain hemorrhage shortly afterwards.

ReplyDeleteLove the blog though- keep up the good work :)

MF.

I'm John Pendlebury's granddaughter and he was executed by the Germans, the story he was wounded by the Germans and died from his wounds was to save my grandmother the pain of knowing what really happened to him .

DeleteFrancesca Pendlebury

Thanks so much for this information. After reading Chubb's account I am inspired to learn more about Pendlebury's life, and indeed his death. I've since picked up a second-hand 1954 edition of his Handbook to the Palace of Minos at Knossos, which I thoroughly enjoyed.

ReplyDeleteNice intervention Francesca. Big fan of your grandfather.

ReplyDelete